|

Charles Dickens: The Life of the Author

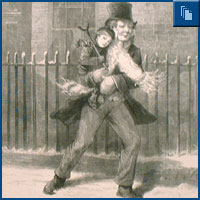

On Top of the World: Oliver Twist to Household Words mode of 'going to work,'" George Cruikshank's original pen-and-ink and watercolor sketch illustrating a scene in chapter 10 of Oliver Twist. NYPL, Berg Collection Throughout his career, Dickens--whose reserves of energy only appeared limitless--worked at such a punishing pace that his health was often seriously compromised. Case in point: as he struggled to finish the first installment of Oliver Twist, while simultaneously coping with family obligations and his responsibilities as the Miscellany's editor, he sent Richard Bentley an update on the morning of January 24, 1837: I have thrown my whole heart and soul into Oliver Twist, and most confidently believe he will make a feature in the work, and be very popular ... I have still a very great deal to do in reading communications, and preparing answers to correspondents; I have done a great deal in altering the papers that will appear, wherever they were weak; and between the one and the other, I really have done, with anxiety and sickness about me, more than nine people out of ten could have performed.  becomes better acquainted with the characters of his new associates, and purchases experience at a high price," Dickens's autograph manuscript of the beginning of chapter 10 of Oliver Twist, the first of his works to be published under his own name. NYPL, Berg Collection. With the huge and varied accomplishment of his first four novels, the world began to listen to Dickens in wonder. Here was a young man of the most modest pedigree and education (without Latin or Greek, as once was said), who had the literary world at his feet. He had become truly famous. How they cheered: Dickens in America  original pen-and-ink and watercolor drawing by George Cattermole, after his wood engraving for Dickens's The Old Curiosity Shop. NYPL, Berg Collection It was, said a witty man, "the greatest affair in modern times, the fullest libation ever poured upon the altar of the muses, the tallest compliment ever paid to a little man." Dickens's reception in America was overwhelming: "I can't tell you what they do here to welcome me," Dickens wrote home to his brother Frederick, "or how they cheer and shout on all occasions--in the streets--in the Theatres--within doors--and wherever I go." There were some censorious mutterings about--at least by American lights--his rather foppish appearance, as evidenced by the longish hair, which was "apparently guiltless of all acquaintance with a brush," the profusion of gold watch-chain, and the garishly hued waistcoats. According to one who was there, the bluebloods of Boston's literary establishment did their best to entertain the great man, but "They were not sorry, however, to pass him on to New York, where a banquet which had been prepared with great elaboration was awaiting him." What awaited Dickens, of course, was the soon-to-be-legendary "Boz Ball."  " the greatest affair in modern times," the legendary "Boz Ball." NYPL, Print Collection But he did forge some warm and lasting friendships during the tour, including with such distinguished American admirers as poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Cornelius Felton, a convivial professor of classics at Harvard. With the latter, Dickens got along so famously that one bemused witness reported of the pair that "they have walked, laughed, talked, eaten Oysters and drunk Champagne together until they have almost grown together--in fact nothing but the interference of Madame D prevented their being attached to each other like the Siamese Twins, a volume of Pickwick serving as connecting membrane."  the appalling Mrs. Sairey Gamp, the tipsy nurse from Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit, including this fanciful drawing of her sudden appearance before a very startled "Phiz." NYPL, Berg Collection This entertaining brouhaha had no lasting effect on Dickens's popularity with his American public. However, readers on both sides of the Atlantic did react coolly to his next serial, Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44; 1844), a novel which boasts some excellently stinging satire (of America) as well as two unforgettable characters, the vile hypocrite Seth Pecksniff, one of Dickens's most hateful creations, and the perfectly awful Mrs. Sairey Gamp, a gin-soaked nurse with a sideline in laying out corpses. A shrewd operator with "a face for all occasions," Mrs. Gamp is also so sublimely the mistress of her own strange vernacular ("Who deniges of it?"), that for many readers, Chuzzlewit is mainly of interest as "the novel that Mrs. Gamp is in." A new gospel: Dickens and Christmas  relating to A Christmas Carol, including this engraving of Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim, executed for an American edition of the work after the drawing of Sol Eytinge, Jr. NYPL, Print Collection Dickens was inundated with heartfelt letters from complete strangers, which John Forster read with wonder--they were not at all literary, Forster would write, but "of the simplest domestic kind." And yet even such literary eminences as Francis Jeffrey, critic and founder of the Edinburgh Review, succumbed to the Carol's benevolent philosophy. The Carol's first readers were moved not only by the tale's verve and sentiment, but also by what was so obviously and appealingly the author's own exhilaration in the telling. In a letter to his American friend Cornelius Felton, dated the day after New Year's in 1844, Dickens writes with merry exuberance of the "Ghostly little book," over which he "wept, and laughed, and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner in the composition." (See adjacent slideshow for the original manuscript of this famous letter.) No writer is more indelibly associated with the spirit of the Christmas holidays, that season of "hospitality, merriment, and open-heartedness," than Dickens, who cultivated the association assiduously. Four more bestselling Christmas Books followed, but none of these little holiday volumes has enjoyed the enduring popularity of the Carol. After The Haunted Man (1848), the last of the Christmas Books, Dickens marked the holidays with stories that were seasonal in spirit, if not in setting, beginning with "A Christmas Tree" (1850), a radiant meditation on the power of the imagination, or fancy, in which the narrator tells us: And I do come home at Christmas. We all do, or we all should. We all come home, or ought to come home, for a short holiday--the longer, the better--from the great boarding-school, where we are for ever working at our arithmetical slates, to take, and give a rest. As to going a visiting, where can we not go, if we will; where have we not been, when we would; starting our fancy from our Christmas Tree! But there was to be no rest for Dickens. He expands his audience

As both an editor and novelist, Dickens had an immediate and unerring sense of his public, and by publishing his novels in inexpensive monthly parts (with hardbound editions to follow), he kept his enormous readership hooked to whatever had just flowed from his pen. It is difficult now to recapture the excitement with which "the new Dickens" was awaited by readers around the world. As a writer for The Daily Telegraph said in 1872, looking back on Dickens's meteoric career: "[H]is current story was really a topic of the day; it seemed something almost akin to politics and news--as if it belonged not so much to literature but to events."

|

||||||||||||||