|

Charles Dickens: The Life of the Author

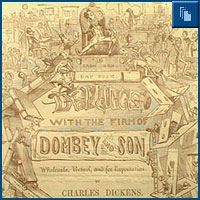

A Fearful Locomotive: The Man Who Never Slept relating to Dombey and Son, including, as shown here, the fifth intallment of its serial run, which closes with the death of Little Paul Dombey. NYPL, Berg Collection With Dombey and Son (1846-48; 1848), Dickens began the procession of more deeply considered and carefully structured novels upon which his reputation rests today. The central idea of the story was that it "should do with Pride what its predecessor [Martin Chuzzlewit] had done with Selfishness." It enjoyed an immense success from the first installment, which appeared in October 1846--as Dickens wrote to a Swiss friend on the 12th, "There is every present reason to suppose it will beat all the other books." Dombey and Son certainly surpassed Chuzzlewit in both critical esteem and sales, and marked a turning point in Dickens's career. He had begun to regain control of his copyrights, which he had signed away too cheaply in the heady flush of his first triumphs, and the continuing sales of his earlier works combined with Dombey's splendid profits began to make him financially prosperous beyond what he could have ever imagined.

While working away at the early stages of Dombey in Paris,

Dickens informed Forster matter-of-factly, "Paul, I shall slaughter

at the end of number five." In the event, the scene proved to

be as affecting for the author as it would be for his readers. On January

18, 1847, Dickens wrote to a dear friend, the philanthropist Angela

Burdett-Coutts: "Paul is dead. He died on Friday night about 10

o'clock, and as I had no hope of going to sleep afterwards, I went

out, and walked about Paris until breakfast time next morning ..." Thus

the "children of his brain" took possession of him. Many

years later, Dickens told his American publisher James T. Fields that

even after his characters had been launched, "free and clear of

him, into the world, they would sometimes turn up in the most unexpected

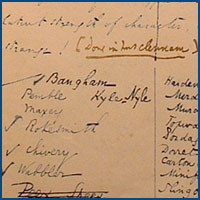

places to look their father in the face."  and I," an original drawing by "Phiz" (Hablot K. Browne), illustrating a scene in chapter 5 of David Copperfield. NYPL, Berg Collection Dombey was followed by David Copperfield (1849-50; 1850), Dickens's own "favourite child," which was greeted with near universal admiration. "If I were to say half of what Copperfield makes me feel tonight," he told Forster, "how strangely, even to you, I should be turned inside out! I seem to be sending some part of myself into the Shadowy World." Written ingeniously in the form of an autobiography, David Copperfield presents the "personal history, adventures, experience, & observation" of a writer who shares much with his creator, but the novel, one of his most touching and to this day most-read works, is in fact, as Dickens remarked, "a very complicated interweaving of truth and fiction." It is often, as well, one of the funniest bildungsromans ever written. After Copperfield came the magnificent panoramic tapestry of Bleak House (1852-53; 1853), a savage indictment of the Court of Chancery and indeed of the entirety of English society; the hard-hitting analysis of the modern industrial order in Hard Times (1854); and the forceful social critique of Little Dorrit (1855-57; 1857), which George Bernard Shaw declared "a more seditious book than Das Kapital." Dickens's book of Memoranda It seems that many of the names he recorded in the notebook were quite real, having been transcribed by him from official documents or other sources; even those that seem the most Dickensian, which ring most absurdly to the modern ear, may well be actual names that Dickens came across during his constant wanderings. For example, the list of names on page 23 of the notebook, beginning Seba is annotated by Dickens, "Girls from Privy-Council Education Lists." Some of the boy's names from the same source: "Pickles," "Doctor," "Samilias," and "Feather." Longer entries in the Memoranda book sketch out conversations (overheard? imaginary?) and plot possibilities, as well as character "snapshots," such as this early evocation of Mrs. Clennam, Arthur Clennam's invalid mother in Little Dorrit, which was most likely written into the Memoranda book before Dickens had actually begun work on the novel: Bedridden (or room-ridden) twenty--five and twenty--years; any length of time. As to most things, kept at a standstill all the while. Thinking of altered streets as the old streets--changed things as the unchanged things--the youth or girl I quarreled with all those years ago, as the same youth or girl now. Brought out of doors by an unexpected exercise of my latent strength of character, and then how strange!

artifacts relating to Little Dorrit, including the wrapper of the final installment of the novel, shown here, a double number published in June 1857. NYPL, Berg Collection When an entry had served its purpose, it was usually scored through, or cancelled; and sometimes Dickens added an explanatory note to the original passage, often years later, as he did at the end of the passage about the woman invalid: "Done in Mrs Clennam." There are also two entries in Dickens's Memoranda book that offer a particular fascination, because they may--may--be autobiographical. There is no way to decide the question definitively, but in any case, there is nothing else like them in the notebook. One of these passages, probably dating from around May 1855, may give voice to Dickens's profound unease at this time of his life, just as he was about to tackle--or had just begun--the first installment of Little Dorrit: The man who is incapable of his own happiness. One who is always in pursuit of happiness. Result. Where is happiness to be found then. Surely not everywhere? Can that be so, after all? Is this my experience? The passage was never cancelled. The demon of delightfulness

Bobadil, the consummate military braggart, in Ben Jonson's comedy Every Man and His Humour, an engraving after the painting by C.R. Leslie, R.A. NYPL, Print Collection The novels brought him wealth and worldwide fame, and for anyone else this would have been achievement (and labor) enough. But Dickens's restiveness could not be checked, and throughout his life he threw himself into a staggering array of activities, both personal and professional, over and above the supreme and concentrated dedication with which he made himself the most beloved author of his age. To begin with, as friends and family amply attested, he was a consummate host, one whose high spirits were irresistibly contagious--"Never was there, surely," asserted one of his most faithful admirers, "at any time, such a Master of Revels." In company, said another, Dickens "talked like a demon of delightfulness." Dickens too was always mad for the stage--"there never was a more assiduous playgoer" declared one friend. As a young man he had even contemplated a career as an actor, assuring the management of Covent Garden Theatre that he was endowed with "a natural power of reproducing in his own person what he observed in others." This passion for the theater found expression in the amateur theatricals (mounted both for charity and simply for the sheer joy of it) into which he poured his great gifts as actor, director and producer. He had to have a hand--it seemed--in everything. When, for example, Dickens and his friends got up a production of Ben Jonson's Everyman and His Humor in the autumn of 1845, John Forster was amazed by his high spirits and the relentless zeal with which he threw himself into "the whole of it without an effort." Dickens not only acted brilliantly, but: "He was stage-director, very often stage-carpenter, scene-arranger, property-man, prompter, and bandmaster ... he assisted carpenters, invented costumes, devised playbills, wrote out calls ..."

Dickens loved to tramp about London and the countryside at all hours of the day and night, often for miles and miles at a stretch ("If I couldn't walk fast and far I should just explode and perish."), and his zest for life and his curiosity were illimitable. In the words of George Augustus Sala (one of the young authors he took on at Household Words), Dickens was to be seen everywhere: in "all lodging-houses, station-houses, cottages, hovels, Cheap Jacks' caravans, work-houses, prisons, school-rooms, chandlers' shops, back attics, barbers' shops, areas, back-yards, dark entries, public-houses, rag-shops, police-courts, markets in poor neighborhoods." Moreover, his family was large (nine surviving children, with multitudes of other kin), his circle of friends immense, his adoring fans legion, his workload mindboggling, and his ability to pull it all off positively daemonic. It almost goes without saying that Dickens was an indefatigable letter writer--and indeed, as Lionel Trilling once remarked, "the mere record of his conviviality is exhausting." (Oxford University Press's recently completed 12-volume Pilgrim Edition of The Letters of Charles Dickens is a monumental and magnificent tribute to one of the liveliest and funniest letter writers ever to have applied pen to paper in the history of the English language.) And the social consciousness so vividly present in the novels was not merely a literary device: Dickens devoted himself to numerous charitable enterprises and was very generous to individuals in need, not least to members of his own family. A friend would recall a face that blazed with indignation at any injustice or cruelty. Under the muzzle  after the somber portrait photograph by John and Charles Watkins dating from 1861. NYPL, Berg Collection

Contemporary observers invariably remarked upon Dickens's ebullience, his gusto for life and his irrepressibly comic spirit--qualities seemingly never caught by the camera, no matter how handsome or distinguished the portrait. In Pen Photographs of Charles Dickens's Readings: Taken from Life (1871), the witty and perceptive American journalist and writer Kate Field offered a caution: If anybody thinks to obtain an accurate idea of Dickens from the photographs that flood the country, he is mistaken. He will see Dickens's clothes, Dickens's features, as they appear when Nicholas Nickleby is in the act of knocking down Mr. Wackford Squeers; but he will not see what makes Dickens's face attractive, the geniality and expression that his heart and brain put into it. In his photographs Dickens looks as if, previous to posing, he had been put under an exhausted receiver and had had his soul pumped out of him. This process is no beautifier. Therefore let those who have not been able to judge for themselves believe that Dickens's face is capable of wonderfully varied expression. Hence it is the best sort of face. His eye is at times so keen as to cause whoever is within its range to feel morally certain that it has penetrated his boots; at others it brims over with kindliness ... [T]here is a twinkle in it that, like a promissory note, pledges itself to any amount of fun--within sixty minutes. After seeing this twinkle I was satisfied with Dickens's appearance, and became resigned to the fact of his not resembling the Apollo Belvedere. Strangely ill-assorted It is not only that she makes me uneasy and unhappy, but that I make her so too--and much more so. She is exactly what you know, in the way of being amiable and complying; but we are strangely ill-assorted for the bond there is between us. Friends and family were understandably divided in their loyalties; but, what should have remained a private trauma blossomed into a public scandal, not least because of Dickens's constant and blundering efforts to justify himself, in both private and in the press.

Throughout the entire imbroglio, Dickens behaved strangely and often inexcusably--for one preparing a private statement, which of course leaked to the press, impugning Catherine's character and even her mental stability. In later life, his daughter Katey looked back on this awful time and the "madman" who was her father: "This affair brought out all that was worst--all that was weakest in him. He did not care a damn what happened to any of us." On June 12, 1858, a column by the conductor of Household Words stated simply that "some domestic trouble of mine, of long-standing," has "lately been brought to an arrangement." It was as simple as that; from this point, Catherine essentially disappeared from Dickens's life, although he did provide for her generously. Georgina Hogarth stood by her brother-in-law. One newspaper thundered: "Let Mr Dickens remember that the odious--and we might almost add unnatural--profligacy of which he has been accused, would brand him with lifelong infamy ..." But in the end his reputation remained virtually unscathed, and the affection and loyalty of his vast readership intact. At the end of this tumultuous year, Dickens wrote to Mary Boyle, a trusted confidante: "Constituted to do the work that is in me, I am a man full of passion and energy, and my own wild way that I must go is often--at the best--wild enough." When the Dickens household broke up, Katey and her sister Mamie remained with their father, who claimed that both hardened into "stone figures of girls" whenever they came near the "fatal atmosphere" of their mother. Dickens often expressed disappointment with his sons, who seemed to have a hard time of it making their way in the world, but he was deeply attached--and very proud of--his two daughters.

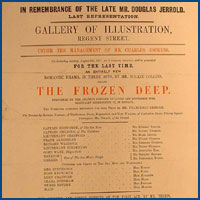

("Mamie") and Kate ("Katey"), on the lawn at Gad's Hill Place, ca. 1865. NYPL, Berg Collection Spirited, forthright and clever, Katey very much took after her father, who called her "My Lucifer Box" in tribute to her formidable temper. She once confided that the only fault she found with her father was that "he had too many children"--and it has been well said that for Dickens, the children of his imagination came before the children of his flesh and blood. Katey distressed her father by marrying Charles Collins, an artist and the brother of his intimate friend Wilkie Collins, but Mamie never left home. "My love for my father," she said, "has never been touched or approached by any other love. I hold him in my heart of hearts as a man apart from all other men, as one apart from all other beings." The year before the separation from Catherine, Dickens met Ellen Ternan, an attractive 18-year-old actress who had been engaged for the Manchester performances of The Frozen Deep. Dickens was very taken with her, and she eventually became his mistress. The liaison raised not a few Victorian eyebrows, leading Dickens to blast the inevitable scandalmongering as "abominably false." Secrecy was, of course, paramount. Ternan was all but erased from Forster's reverential Life of Charles Dickens (1872-74), except for the fact that hers was the first legacy mentioned in the great man's will, which, without comment, Forster included as an appendix to his biography.

|

||||||||||||||