|

Charles Dickens: The Life of the Author

Boz Takes Off Like a Rocket: The Sketches and PickwickHis formal education complete at fifteen, Dickens found a position as a clerk at the office of Ellis and Blackmore, solicitors at Holborn Court, Gray's Inn. Finding the law "a very little world, and a very dull one," he entertained himself by leaning out the window and dropping cherry pits on passersby. He also convulsed his coworkers by mimicking, with uncanny and dead-on perfection, any- and everyone he saw on the streets of London. Here was a foretaste of the protean novelist who would create a veritable army of characters to inhabit Dickens-Land, ranging from the most angelic of tots to the foulest of murderers, and everything in between to be sure. (As Chesterton said, Dickens did not "point out things, he made them.") We also see a hint of the great actor to come, of his dazzling attractiveness to audiences in both amateur theatricals (a great passion) and in the public readings from his own works that would make him a wealthy man.

"There never was such a shorthand writer," marveled one reporter. It was this "wholesome training of severe newspaper work" (as Dickens joked late in life) that launched his career. In his early 20s, Dickens began to publish occasional, and most amusing, stories and sketches that, when they were first collected as Sketches by Boz in 1836, were hailed by one reviewer as "a perfect picture of the morals, manners and habits of a great portion of English Society." It was also noted that the young author possessed (not unlike his mother) "a strong sense of the ridiculous." The Sketches enjoyed a great success, which was certainly due as well to the delightful illustrations that accompanied them. In his preface to the first collection, Dickens wrote that "the Author of these volumes throws them up as his pilot balloon, trusting it may catch favourable current, and devoutly and earnestly hoping it may go off well...." Admitting to "no inconsiderable feeling of trepidation at the idea of making so perilous a voyage in so frail a machine," he secured, as the preface graciously continued, the "assistance and companionship" of a well-known individual who had contributed to the success of similar undertakings in the past, namely George Cruikshank.  Detail from a sheet of George Cruikshank's portrait sketches of Charles Dickens, drawn from life, April 1837. NYPL, Berg Collection Cruikshank, who would next work with Dickens on Oliver Twist (1837-39; 1838), is only one of the many gifted artists whose names will be linked forever with Dickens's. Acclaimed from the beginning of his career for the vividly pictorial quality of his writing, Dickens understood the importance and the value of the image. In 1858, perhaps with a little exaggeration, he declared that there were very few debates in Parliament "so important to the public welfare as a really good picture." "I have also a notion," he continued, "that any number of bundles of the driest legal chaff that was ever chopped would be cheaply exchanged for one really accessible, really humanising, really meritorious engraving." He would collaborate brilliantly and for the most part smoothly with his many illustrators; and in fact only two of his major works of fiction--Hard Times (1854) and Great Expectations (1861)--were first published without illustrations. Pickwick triumphant The first of Pickwick's twenty numbers (the last a double issue) was published on March 31, 1836; and the original intention had been that Dickens's text was to be written to the order of Seymour's drawings. But soon it was the incomparable gallery of originals, with Samuel Pickwick as cynosure, whose "perambulations, perils, travels, adventures and sporting transactions" Dickens narrated with such exhilarating humor and dash, that all England was talking about. It was Seymour who had originally suggested the storyline of a Cockney hunting club, which became The Pickwick Papers, but he committed suicide early in the production of the series. His successor, Hablot K. Browne, would soon adopt the sobriquet "Phiz" to harmonize with Dickens's "Boz"--the beginning of a brilliant partnership between author and illustrator that would be sustained for twenty-three years and nine more novels, coming to a close with A Tale of Two Cities (1859). Pickwick was a publishing phenomenon, and it appealed to everyone, even the most discriminating reader. As an early enthusiast, one Miss Mitford, observed: "It is fun--London life--but without anything unpleasant: a lady might read it aloud ... All the boys and girls talk his fun ... and yet they who are of the highest taste like it the most." And the critics too were generally more than enthusiastic. Sydney Smith, for one, announced that "The Soul of Hogarth has migrated into the Body of Mr Dickens" (linking Dickens to the great visual artists of the past would become a critical commonplace). As the exultant author was able to report, in well-deserved capitals: "PICKWICK TRIUMPHANT." Dickens emerges

Strangely, it was Kate's younger sisters--Mary and Georgina--who were much more powerful presences in Dickens's life.

With Pickwick, Dickens had unquestionably arrived. His vision certainly darkened as his artistry matured, the satire growing increasingly slashing and the critiques of social injustice more trenchant, while the panoramic presentation of "great portions" of English society, even its grimmest corners and byways, would become only more masterful in the novels that followed the early triumphs. But for the young Dickens, the exuberantly good-humored Pickwick held a special place in the affections (as indeed it does for many Dickensians).

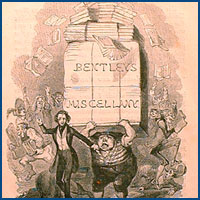

An advertising circular, written by Dickens, promoting the recently launched Bentley's Miscellany, showing its inaugural editor, as drawn by Phiz, leading a porter groaning under a huge crate laden with copies of the new magazine. NYPL, Berg Collection Three days later, on November 4, Dickens signed an agreement with the publisher Richard Bentley, who had been observing the extraordinary rise of "Boz" with keen interest. Bentley wanted Dickens to take on the editorship of a new magazine he planned to launch, which at first was to be called Wits' Miscellany. Dickens finally accepted the offer, on the condition that his new responsibilities did not interfere with Pickwick, which still had a year to go in its serial run. Always a shrewd businessman, Dickens well knew his worth, as he reminded Bentley in a letter setting out his terms: "I need not enlarge on the rapidly increasing value of my time and writings to myself, or on the assistance 'Boz's' name just now, would prove to the circulation, because I am persuaded that no one is better able to form a correct estimate of both points, than you are." Dickens agreed to sign on for one year only (in the event, he lasted

three), with the first number of--as it was finally titled--Bentley's

Miscellany scheduled for January 1837. The next month, in the Miscellany's

second issue, a celebrated literary orphan, one Oliver Twist, would

make his debut.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||