|

Section I Selections from the C.W. McAlpin Collection

Section I Selections from the C. W. McAlpin CollectionSection VAllegorical and Narrative Images of Washington During his lifetime, Washington became an international symbol of the American Revolution and the new republic. Known for his grand physique and customary reserve, he was considered by many to be the very personification of strength of mind and body. His roles as an ardent patriot, a military and executive leader, and a Master Mason were the subjects of many allegorical and narrative prints.

In this cartoon, “Mrs. General Washington” embodies America. She holds a thirteen-strand whip above her head, with which she is about to strike Britannia, the personification of the British Empire. The thirteen strands allude to the thirteen stripes on the American flag, which denote the original American colonies. Behind Mrs. Washington stand three male figures representing the Netherlands, France, and Spain. Each one utters words of encouragement, as Mrs. Washington berates Britannia: “Parents Should not behave like Tyrants to their Children,” to which Britannia responds: “Is it thus my Children treat me.” This cartoon was published in The Rambler’s Magazine, a monthly periodical published in London starting in January 1783. The journal’s full title was The Rambler’s Magazine; or, The annals of gallantry, glee, pleasure, and the bon ton; calculated for the entertainment of the polite world; and to furnish the man of pleasure with a most delicious banquet of amorous, Bacchanalian, whimsical, humorous, theatrical and polite entertainment.

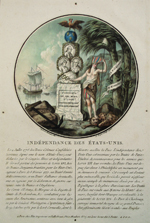

This print celebrates the signing of two treaties between the United States and France on February 6, 1778: the Treaty of Amity and Commerce, and the Treaty of Alliance. (The accompanying text erroneously gives the date as 1777.) The former acknowledged the United States as an independent nation, and promoted trade between the two countries; the latter ensured a military alliance between them against Great Britain, specifying American independence as a condition of peace, while also requiring that France and the United States be in agreement on any peace arrangement. The woman depicted in the print represents America. Both the liberty pole in her left hand and her left foot rest on the lion representing Britain. The medallion portraits affixed to the marble monument depict Louis XVI (1754–1793), King of France from 1774 to 1792; Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790); and Washington (misspelled “Waginston”). Franklin, who served as minister to France during the Revolution and was a highly regarded presence there, played an essential role in securing French military and financial aid for his country. The cock and fleurs-de-lis atop the column are symbols of France.

Freemasonry is an international secret fraternity that promotes liberal and democratic principles among its members. Unlike Williams’s Masonic portrait of Washington, reproduced in O’Neill’s etching on view here, this print focuses entirely on symbolic references to the Masonic order, most of them based on instruments of the stonemason. By 1765 Masonic orders existed in all of the thirteen colonies. Many Revolutionary figures were members, including Franklin, Hancock, and Revere. Washington was initiated as a Freemason in Virginia in 1752, and the following year he became a Master Mason. He is depicted here (with facial features based on Stuart’s “Athenaeum” portrait) in that capacity, his status indicated by the ornament hanging around his neck, his position at the top of three steps, and the letter “G” above his head, an abbreviation for both “God” and “geometry.” The rough stone block on his right represents man in his natural state, prone to irrational thought, while the smooth, squared stone on his left represents man after exposure to Freemasonry, now a useful building block for a stable society. The positions of his hands and feet may allude to secret gestures of the fraternity.

This print is notable for being one of the largest and most complex of its time in this country. Doolittle managed to present a great deal of information with clarity, and in an original and appealing format that he could update with ease. At least six states, or versions, were published. In the first, Doolittle depicted Washington’s head in three-quarter view. In this, the second, he replaced that portrait with a profile derived from Joseph Wright’s print of 1790, also on view here. The rings in the chain around the portrait contain the names and seals of the original thirteen states, along with the number of inhabitants, senators, and representatives. With each printing, this information was updated, and statistics for new states or territories were added to an existing ring or in the margin outside the chain. Shortly after the inauguration of John Adams in 1797, Doolittle published a new version with the second president’s portrait.

According to a mutual friend of Washington and Charles Buxton, this image was designed to “perpetuate the idea of the American Revolution.” The figure of Washington stands on a pedestal holding his farewell address in his right hand, his head derived from Stuart’s “Athenaeum” portrait. Much of the architectural framework alludes to Masonic symbolism, and therefore Washington’s membership in the fraternity, while the remaining imagery, of a familiar vocabulary, refers to his roles as the military leader of the Revolution and the nation’s first president. The American eagle at the top holds in its beak a banner with the words “E Plur[ibus] Unum” and, below, the names of the current sixteen states of the Union. Behind Washington is a view of Bowling Green, and the evacuation of the British fleet from New York on November 25, 1783. The empty pedestal once bore a statue of George III, toppled by angry citizens in 1776. Washington’s position on a pedestal therefore indicates that he has replaced the king as the authority of the American colonies.

In this scene Washington personifies Patriotism; Frederick II, Fortitude; and William Pitt, Wisdom. Frederick II (1712–1786), also known as Frederick the Great, ruled as King of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, and is widely regarded as the greatest military strategist and general of the 18th century. The British statesman William Pitt (1708–1778), first earl of Chatham, was a highly esteemed war minister and orator. Concerning the American colonies, he opposed the ill-fated Stamp Act and Townshend Acts, encouraged appeasement of the colonies, and, upon the outbreak of the Revolution, urged a peace settlement, though not as far as granting independence to the colonies. The magazine or book for which this print served as frontispiece remains unknown. A similar scene, but with Washington, Nathanael Greene, and Alexander Hamilton personifying Patriotism, Fortitude, and Wisdom, is the frontispiece to A Compendium of the History of All Nations … by Donald Fraser, published in New York in 1807.

This print was published as the frontispiece to the first issue of The Philadelphia Magazine, in which the magazine’s publisher, Benjamin Davies, described a “splendid public dinner,” given by “the merchants of Philadelphia” on March 4, 1797, in honor of Washington, who had just retired from the presidency. According to Davies, the decoration at Rickett’s Circus, the venue for the festivities, included a life-size transparency depicting a scene very much like the one in this print. It is possible that Barralet himself, who was active in this country from 1795, and had experience as a stage designer, created the transparency at Rickett’s, and that this print is based on that piece, or a smaller-scale copy of it. The image portrays Washington standing before the figure of America, who holds a calumet, or Native American peace pipe, in her right hand. At Washington’s feet lie a helmet and sword, representing his military and executive roles, which he now leaves in favor of retirement at Mount Vernon, to which he gestures with his left hand. The eagle, federal shield, and cornucopia in the foreground are symbols of the United States.

This rare and unusual allegorical print, which has been erroneously attributed to the engraver J. P. Elven after a painting by H. Singleton, is a patchwork of symbols and classical imagery. The seated figure of Washington bears little resemblance to the president, but instead evokes the Roman emperor Julius Caesar, as well as the Hebrew prophet and lawgiver Moses. Here Washington presents the Constitution to America, personified by the figure reclining in the foreground with its back to the viewer. The figure to Washington’s right is probably Britannia, her arm resting on a lion, the symbol of the British Empire. Behind him stand three female figures carrying a fasces, a mirror, and what appears to be a lyre. At the right of the image sit three more female figures, holding a square, a mallet, and a palette, symbolizing architecture, sculpture, and painting. To the right of this group stands the Greek goddess Athena, often identified with war and peace, wisdom, the arts, and law and order. Athena gazes up at Hermes, the messenger of the Greek gods, as well as the god of travelers, merchants, and commerce. Hermes points his caduceus toward the temple of fame. At the top of the image hovers an angel, blowing a horn and holding a shield that bears the American emblem.

|