|

Section I Selections from the C.W. McAlpin Collection

Section I Selections from the C. W. McAlpin CollectionSection IVFictitious Portraits of Washington General Washington’s fame reached Europe before any accurate portraits of him did. Lacking any examples of his actual appearance, foreign publishers commissioned fictitious portraits. As early as 1775, publishers in London were already issuing prints of American Revolutionaries that bore no resemblance to the men themselves. These prints then served as models for printmakers elsewhere in Europe. In a similar vein, some American printmakers who had access to reproductions of life portraits chose not to copy them faithfully, but to use them simply as a starting point for decorative or allegorical creations.

The publisher of this fictitious representation of Washington claimed a fraudulent attribution in order to give it a sense of authenticity. The inscription “Done from an Original, Drawn from the Life by Alexr. Campbell of Williamsburgh in Virginia” is entirely false. No such artist is known to have existed, and Washington himself denied having ever met Campbell, let alone posing for him. With good humor Washington declared in a letter: “Mr. Campbell, whom I never saw to my knowledge, has made a very formidable figure of the Commander-in-Chief, giving him a sufficient portion of terror in his countenance.” This print, along with a three-quarter–length portrait of Washington by “Campbell,” was widely circulated in Europe, inspiring many copies and variations, including the following print by Johann Martin Will.

Will clearly based this representation of Washington on the fictitious equestrian portrait by “Campbell.” For his version, published in Germany, Will included an inscription in French and German that appears to taunt Great Britain and question that country’s prospect of victory over the colonies.

Charles Henry Hart likened this print to portraits of William III (1650–1702), King of England, Scotland, and Ireland (r. 1689–1702). It certainly bears more resemblance to equestrian portraits of European monarchs of that period than to Washington or any of his contemporaries. The inscription states that Washington was nominated as ruler by Congress in February 1777. In fact, he was selected by Congress as commander in chief in June 1775, and elected president by the electoral college in April 1789. February 6, 1778, marked the date of France’s alliance with the United States.

Although a representation of Washington in 16th-century European armor may seem laughable, this print, as evidenced by the inscription, was inspired by a commission by the Continental Congress. In 1783, shortly before the signing of the Treaty of Paris, Congress voted unanimously to erect an equestrian statue of Washington and, according to its Journal of August 7, decided “That the statue be of bronze: The General to be represented in a Roman dress, holding a truncheon in his right hand, and his head encircled with a laurel wreath.” Norman, if he was in fact the author, based the head on Charles Willson Peale’s 1776 portrait of Washington (on view here in a mezzotint attributed to Joseph Hiller). His solution for “Roman dress” was a figure in armor that he copied, along with the background battle scene, directly from an engraving by William de la More in John Guillam’s Display of Heraldry, a 1724 edition of which was in the possession of Norman’s acquaintance John Coles, Sr. Armor is also a timeless symbol of military strength, and therefore emblematic of Washington’s prowess as general.

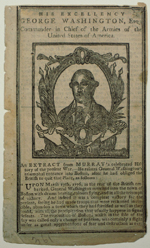

Charles Willson Peale’s 1776 painting was the first life portrait of Washington to be copied in American prints, and it was done so extensively, beginning with the mezzotint attributed to Joseph Hiller, also on view here. These copies, many only vaguely reminiscent of the original painting, appeared in numerous books, almanacs, and primers. In this print, which first appeared in a 1781 almanac and subsequently in a number of New England primers of the 1780s and 1790s, the Washington portrait has been greatly simplified as a little decorative relief cut for insertion in the text. It was probably engraved from type metal by Paul Revere, the Boston silversmith, printer, and Revolutionary. Revere based the image on an engraving for the 1780 Philadelphia almanac by John Norman, which in turn was based on Peale’s portrait.

|