The

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts > Italian

Dance

Development of Ballet Narrative

Portrait of Salvatore Viganò

Salvatore Viganò

Engraving,

[n.d.] Born in Naples to a family of dancers and musicians, Salvatore Viganò danced

for several years in his father's company. In the late 1780s,

he came under the influence of Jean Dauberval, whose approach

to the integrated ballet narrative he would both assimilate

and transform. Viganò spent the better part of the following

decade in Vienna, where in 1801 he choreographed

The Creatures of Prometheus,

set to a score by Beethoven and an early example of

coreodramma (choreodrama). He

brought this new form of danced narrative to its apogee at

La Scala, where he worked for more than fifteen years. Here,

in works such as

Otello (Othello),

Dedalo (Daedalus),

La

Vestale (The Vestal Virgin), and

I Titani (The

Titans), he created what his nineteenth-century biographer,

Carlo Ritorni, called "a sublime...expression of poetic

ideas and dramatic situations." Cia Fornaroli Collection,

Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Maria Medina

Viganò as Terpsichore

Sepia engraving

by Carl Pfeiffer after a painting by Joseph Dorffmeister,

Vienna, 1794. Maria Medina was a Spanish dancer

who married the Italian choreographer Salvatore Viganò in

the late 1780s and performed with him in many successful

productions during the next decade. In this image she wears

the sandals and light diaphanous gown that revolutionized

ballet costume after the French Revolution. The new dress,

which referred both to contemporary fashion and classical

antiquity, allowed the ballerina to move with new freedom. Jerome

Robbins Dance Division.

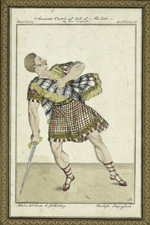

Armand

Vestris in Macbeth

Vestris

Color engraving,

[Naples, ca. 1819]. The

grandson of Gaetan and the son of Auguste Vestris, Armand

followed the family tradition by training as a professional

dancer. He spent several years in London,

mounting several successful ballets at the King's Theatre

and marrying the comic actress Lucia Elizabetta Bartolozzi,

who as Madame Vestris became a well-known London theatrical figure. He spent the last years of his life in Italy, where he staged

Macbeth, and Vienna, where he died. Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Gasparo Angiolini

Born in Florence in 1731, Gasparo Angiolini began his dance

career in Lucca and performed throughout northern Italy,

before making his way to Vienna in the early 1750s. Here,

at the Hoftheater, he came under the creative influence of

Franz Hilverding, whose ballets successfully integrated mime,

movement, and characterization in short narratives. In 1758,

when Hilverding left for St. Petersburg, Angiolini succeeded

him as ballet master. Gradually, his own creative voice

began to emerge. In 1761, he choreographed

Don Juan,

ou Le Festin de Pierre (Don Juan, or The Stone Banquet),

the first of several works to the music of Christoph Willibald

Gluck. Two years later he created the dances to

Orfeo

ed Euridice (Orpheus and Eurydice), and in 1765 he worked

with the composer on the ballet-pantomime

Sémiramis and

the ballet

Iphigénie en Aulide (Iphigenia at Aulis). In

his preface to

Don Juan, Angiolini, through the pen

of the writer and librettist Raniero de Calzabigi, identified

his work with the ideals of ancient pantomime, an "art...express[ing]

the customs, the passions, the actions of gods, heroes, human

beings through movements and body postures, through gestures

and signs done rhythmically and appropriate for the expression

of that which one wishes to represent." He coined the

phrase "

danza parlante," reflecting his

belief that the dance must speak. At the same time, he insisted

that the artist had to make the action "visible."

Angiolini spent several years in St. Petersburg, before

returning to Italy. He produced several ballets in Venice

and in 1773, in Milan, published the volume of Letters...to

Monsieur Noverre, in which he challenged Jean-Georges

Noverre's assertion of being the originator of the ballet

d'action, claiming this honor instead for his mentor

Hilverding. Noverre's sharply polemical response, published

in 1774, marked the start of a long and bitter controversy. In

1774 Angiolini returned to Vienna as successor to Noverre,

who had been invited to Milan. Noverre's ballets were poorly

received, and his contempt for Italy's celebrated grotteschi,

whose combination of virtuosity and corporeal expressiveness

represented a form of danced action, did not endear him to

Italian audiences. He left Milan in disgrace. Angiolini

did not fare much better in Vienna, where partisans of Noverre

jeered his ballets and intrigued against him. He soon returned

to St. Petersburg, where he fulfilled two lengthy engagements

in the 1770s and 1780s. Between these Russian sojourns,

Angiolini produced a number of ballets in Italy, especially

at La Scala. A democrat and a republican, Angiolini was

imprisoned in 1799 and exiled from Milan, although he later

returned to die there.

Gasparo Angiolini, Dissertation sur les ballets pantomimes

des anciens, pour servir de programme au ballet pantomime

tragique de Sémiramis, composé par Mr. Angiolini Maître

des Ballets du Théâtre près de la Cour à Vienne, et représenté pour

la première fois sur ce Théâtre le 31 Janvier 1765. A

l'occasion des fêtes pour le mariage de sa majesté, le

Roi des Romains (Dissertation on the pantomime ballets

of the ancients, to serve as the program for the tragic

ballet pantomime Sémiramis, composed by Mons. Angiolini,

Ballet Master of the Court Theater in Vienna, and represented

for the first time at this Theater on 31 January 1765,

on the occasion of the marriage of His Majesty, King

of the Romans).Vienna, 1765. This was the first

ballet item acquired by Walter Toscanini and his first

gift to Cia Fornaroli. Note the collector's distinctive

ex libris. Cia Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins

Dance Division.

Gasparo Angiolini, Lettere di Gasparo Angiolini a

Monsieur Noverre sopra i balli pantomimi (Letters

from Gasparo Angiolini to Mons. Noverre on ballet pantomimes).Milan,

1773. In this polemical volume, conceived in the form

of letters, Angiolini disputed Jean-Georges Noverre's

claim to be the founder of the ballet d'action (or

narrative ballet). Walter Toscanini acquired many documents

related to the Angiolini family and wrote a biography

of the choreographer that remains unpublished. Cia Fornaroli

Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Jean-Georges Noverre, Lettres sur la danse et sur

les ballets, par M. Noverre, Maître des Ballets de Son

Altesse Sérénissime Monseigneur le duc de Würtemberg,

et ci-devant des Théâtres de Paris, Lyon, Marseille,

Londres, etc. (Letters on Dancing and Ballets, by

Mons. Noverre, ballet master to His Most Serene Highness

the Duke of Würtemberg, and formerly of Theaters of Paris,

Lyon, Marseille, London, etc.).Vienna, 1767. Bookplate

of Baron Greg.re de Stroganoff. Stamped on

the title page in Russian "Biblioteka universiteta

sibirskago" (Library of the University of Siberia). Cia

Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance Collection.

Portrait

of Salvatore Viganò

Engraving,

[n.d.] Born in Naples to a family of dancers and musicians, Salvatore Viganò danced

for several years in his father's company. In the late 1780s,

he came under the influence of Jean Dauberval, whose approach

to the integrated ballet narrative he would both assimilate

and transform. Viganò spent the better part of the following

decade in Vienna, where in 1801 he choreographed The Creatures of Prometheus,

set to a score by Beethoven and an early example of coreodramma (choreodrama). He

brought this new form of danced narrative to its apogee at

La Scala, where he worked for more than fifteen years. Here,

in works such as Otello (Othello), Dedalo (Daedalus), La

Vestale (The Vestal Virgin), and I Titani (The

Titans), he created what his nineteenth-century biographer,

Carlo Ritorni, called "a sublime...expression of poetic

ideas and dramatic situations." Cia Fornaroli Collection,

Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Interior

of La Scala During the Last Act of Salvatore Taglioni's

Ballet The Conquest of Malacca, with Scenery by

Alessandro Sanquirico

Aquatint engraving

from the album Raccolta di scene teatrali eseguite o disegnate

dai più celebri pittori scenici in Milano (Collection

of Theatrical Scenes Executed or Designed by the Most Celebrated

Scene Painters in Milan), Milan,

1820. The queen of Italian theaters, La Scala opened in Milan

in 1778. With its half-dozen tiers the theater was huge,

and its productions in every way spectacular. This view

of the house shows the shipwreck that concluded Salvatore

Taglioni's 1820 ballet The Conquest of Malacca. The

scenery was designed by Alessandro Sanquirico, La Scala's

maker of theatrical marvels during the early nineteenth century. Cia

Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Designs

by Alessandro Sanquirico

Chamber

in the Palace of Memphis in Salvatore Viganò's Tragic Ballet Psammi, King of Egypt,

1817

Aquatint engraving

of a set design by Alessandro Sanquirico, Milan, [1817?]. Most of Viganò's ballets had historical subjects,

and many were set in antiquity. Sanquirico's designs, drawing

upon an Italian scenic tradition that originated in the seventeenth

century, combined historical fidelity and architectural grandeur,

underscoring the heroic dimension of Viganò's poetics. Cia

Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

A

Delightful Place: Scene from Salvatore Viganò's Mythological

Ballet The Titans, 1819

Aquatint engraving

of a set design by Alessandro Sanquirico, Milan, [1819?]. Staged only two years before Viganò's death, The

Titans merged classical myths and Biblical themes in

a narrative set at the dawn of humanity. In this pastoral

scene, Sanquirico conveys Viganò's skillful handling of groups,

emphasis on expression, and use of spatial counterpoint and

asymmetry. The classical iconography recalls Renaissance

painting and looks forward to the "Greek" dances

of Isadora Duncan and Michel Fokine in the early twentieth

century. Cia Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance

Division.

Hanging Gardens with Baths in Memphis in Salvatore Viganò's

Tragic Ballet Psammi, King of Egypt, 1817

Aquatint

engraving of a set design by Alessandro Sanquirico, Milan,

[1817?]. Cia Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance

Division.

The Palace

of Venus in Salvatore Taglioni's Anacreontic Ballet Pelius and Miletus,

1827

Aquatint engraving

of a set design by Alessandro Sanquirico, Milan, [1827?]. Although identified with the eighteenth century,

anacreontic ballets--or ballets on mythological subjects

with amatory themes--remained a recognized genre in the nineteenth. Sanquirico's

celestial finale to Salvatore Taglioni's Pelius and Miletus,

with flying cupids, floral streamers, sculptured columns,

and even swans, depicts the Apotheosis of Venus with a profusion

of richly imagined detail. Cia Fornaroli Collection, Jerome

Robbins Dance Division.

Lettere critiche intorno al Prometeo, ballo del Sig.

Viganò (Critical letters concerning Prometeo, a ballet

by Mr. Viganò). Milan, 1813. The authorship of this

volume is ascribed to Giulio Ferrario, a distinguished

librarian and author of a multivolume work on ancient

and modern Italian costume. Cia Fornaroli Collection,

Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Prometeo, ballo mitologico inventato e posto sulle

scene del R. Teatro alla Scala da Salvatore Viganò nella

primavera dell'anno 1813 (Prometeo, a mythological

ballet invented and staged at the Royal Theater of La

Scala by Salvatore Viganò in the spring of the year 1813). Milan,

[1813?]. Viganò choreographed The Creatures of Prometheus to

a commissioned score by Beethoven in 1801 at Vienna's

Hofburgtheater. Twelve years later at La Scala, Viganò created

a new version of the heroic-allegorical work, now called

simply Prometeo (Prometheus), which critics hailed

as one of the choreographer's masterpieces. However,

instead of using the original music, Viganò crafted a

score to support the choreography, adding to four of

Beethoven's original pieces, other compositions by Mozart,

Haydn, Beethoven, Gluck, Josef Weigl, and himself. The

cast list in the published libretto for the La Scala

production displays the typical division of ranks in

Italian companies of the period. Cia Fornaroli Collection,

Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

La Vendetta di Venere, gran ballo composto e diretto

al R. Teatro alla Scala, dal Sig.r Salvatore

Viganò (musica di diverse rinomati autori). Ridotta

per Cembalo Solo dal Sig.r Ferd.o Bonazzi. Dedicato

dall'Editore Al Merito singolare della Sig.a Elena

Viganó (The Revenge of Venus, grand ballet composed

and directed at the Royal Theater of La Scala by Mr.

Salvatore Viganò [music by various renowned authors]. Reduction

for solo harpsichord by Mr. Ferdinando Bonazzi. Dedicated

by the Publisher to the singular merit of Ms. Elena Viganò). Milan,

[ca. 1817]. An arrangement of musical excerpts from

Viganò's ballet Mirra, ossia La Vendetta di Venere (1817)

by Rossini, Beethoven, Josef Weigl, Michael Umlauff,

and Michele Caraffa. Elena Viganò, to whom this harpsichord

reduction was dedicated, was the choreographer's daughter

and also a dancer. The Viganò family was one of many

multigenerational dance dynasties that left a deep mark

on Italian ballet. Emerging in the eighteenth century

with Salvatore's father Onorato, the Viganòs remained

active in the field until the late nineteenth century. Cia

Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Nicola Molinari in the title role of Salvatore Viganò's

tragic ballet Otello, ossia Il Moro di Venezia (Othello,

or The Moor of Venice), 1818. I[mperial] R[egio] Teatro

Grande della Scala in Milano, Almanacco, 1821. Nicola

Molinari specialized in roles--of which Othello was the

most famous--that required a superb command of gesture

and mime. He was frequently teamed with Antonia Pallerini,

who played the role of Desdemona. Cia Fornaroli Collection,

Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Antonia Pallerini in the title role of Gaetano Gioja's

tragic ballet Gabriella di Vergy, 1823. I.

R. Teatro alla Scala, Almanacco, 1824. A powerful

actress and mime, Antonia Pallerini appeared in many ballets

by Salvatore Viganò and Gaetano Gioja, as well as works

by the French choreographers Jean-Louis Aumer and Louis

Milon. Cia Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance

Division.

Teresa (Therese) Heberle as Venus in Jean [Giovanni]

Coralli's anacreontic ballet La Statua di Venere (The

Statue of Venus), 1825. I. R. Teatro alla Scala, Almanacco,

1826. Therese Heberle was an Austrian dancer who had trained

and performed since childhood with Friedrich Horschelt's

Viennese Kinderballett (Children's Ballet). She danced

extensively in Italy during the 1820s and early 1830s,

frequently partnered by Jean Rozier. Cia Fornaroli Collection,

Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Domenico Ronzani in Giuseppe Monticini's ballet L'Orfana

di Ginevra (The Orphan Girl of Geneva), staged by

Ronzani at the Teatro La Canobbiana, Milan, 1830. I.

R. Teatro alla Scala, Almanacco, 1831. A dancer

of strong dramatic presence, Domenico Ronzani restaged

a number of Romantic ballets, especially for Fanny Elssler,

as well as the first Roman production of Giselle,

which premiered in 1845 at the Teatro Argentina. Cia

Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

La Tersicore milanese (The Milanese Terpsichore). Milan,

1822. Adelaide Grassi was still a student at the La Scala

school when this hand-colored engraving was made. Also singled

out in this charming pocket almanac were the young dancers

Lucia Rinaldi, Teresa Olivieri Bertini, Maria Lampuzzi, Gaetana

Quaglia, Gaetana Trezzi, Carolina Valenza, Clara Rebaudengo,

and Giovanna Viscardi. Popular for centuries, Italian theatrical

almanacs enjoyed a golden age in the nineteenth century,

publishing images and biographies of leading performers,

commentaries on works, and even dance treatises. With its

highly developed publishing and printing industries, Milan

became Italy's de facto capital even under Austrian rule. Cia

Fornaroli Collection, Jerome Robbins Dance Division.