|

THE HUDSON RIVER: HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

TRADE & TRANSPORTATION

TOURISM

ART & LITERATURE

INTRODUCTION

The

Hudson River region is one of America's treasures. Long before

English explorer Henry Hudson sailed up the river in 1609 for

the Dutch East India Company, the waterway was a major travel

route for Native Americans. While it did not provide the Europeans

with their desired connection to the Pacific, the river opened

trade routes north to Canada and west to the Great Lakes. Until

the Mississippi Valley was settled two centuries later, the Hudson

was America's most prominent, and profitable, waterway. The

Hudson River region is one of America's treasures. Long before

English explorer Henry Hudson sailed up the river in 1609 for

the Dutch East India Company, the waterway was a major travel

route for Native Americans. While it did not provide the Europeans

with their desired connection to the Pacific, the river opened

trade routes north to Canada and west to the Great Lakes. Until

the Mississippi Valley was settled two centuries later, the Hudson

was America's most prominent, and profitable, waterway.

From the beginning, thousands of visitors plied its waters on

their travels. The river's dramatic scenery - the Palisades, the

Hudson Highlands, the Catskills - soon became renowned around

the world, carried on the tongues and in the letters of travelers.

The Hudson and its scenery became a popular subject for artists

and writers, inspired by its beauty and facilitated by its convenience

to the port of New York. As publishing developed in the 19th century,

particularly in New York, the sublime locales along the river

found expression in ink as pictures and travel accounts. As more

prints, poetry and tales were published, more travelers were attracted

to the region, from all parts of the western world. This phenomenon

is now about to enter its fifth century. The enduring popularity

of the river has left an extraordinary historical record, in both

scope and quality. The Hudson River is an often-used term to describe

much of the most distinctive landscape art and regional literature

created in the United States.

TRADE & TRANSPORTATION

|

Claimed by the Dutch, colonized by

feudal patrons, and settled by a mix of immigrants from

Europe and other New World colonies, the Hudson Valley

is a uniquely American cultural region. It played a pivotal

role in winning the Revolutionary War, and the river became

the world's most important commercial waterway when the

Erie Canal opened the way to the American West. The region

evokes images of grandeur and power as the jewel of the

Empire State, yet the everyday familiarity of its "sleepy

hollows" doggedly persists in the collective imagination.

Small homesteads and farms first settled by Dutch and

German immigrants, aristocratic palaces on private estates,

and industry-friendly river towns intermingle to create

a cultural landscape of remarkable diversity and texture.

All of this rich history is situated in the midst of sublime

scenery, which launched American Romanticism and inspired

the world.

The Hudson River extends some 315 miles,

from the headwaters in the Adirondack Mountains at Lake

Tear of the Clouds to its meeting with the Atlantic Ocean

at New York City. The river was one of the principal waterways

in North America, with a prodigious history of commerce,

transportation, culture, and

recreation well before European settlement. In Colonial

times, the river supported a lucrative fur trade and

conveyed Hudson Valley wheat and timber to New York City

from where it was distributed throughout the

|

|

Detail,

map of northeastern United States from Jaques Milbert, Itineraire

Pittoresque du Fleuve Hudson, 1828. |

| Western World. The Hudson's

main tributary is the eastwardflowing Mohawk River; in addition

to Albany and New York, its principal cities are, north

to south, Troy, Hudson, Kingston, Poughkeepsie, Newburgh,

Peekskill and Yonkers in New York State, and Weehawken,

Hoboken and Jersey City in New Jersey. |

| Life on the river was transformed

when inventor Robert Fulton inaugurated a new era of water

navigation in 1807, piloting his North River Steamboat,

later known by its popular name, the "Clermont."

Beginning in 1820, the Erie Canal connected the Hudson to

the Great Lakes and soon after the Delaware & Hudson

Canal linked the river to Pennsylvania coal fields supplying

the raw materials and fuel that transformed New York City

into the great American metropolis. The Hudson's importance

as one of the nation's main arteries of trade continued

to grow. The "DeWitte Clinton" locomotive first

ran on track built along the river's edge. In 1853 the New

York Central Railroad consolidated many smaller lines to

funnel freight and passengers into the city from a rail

network that soon stretched across the continent.

|

|

Hudson

River steamers leaving New York. From Benson J. Lossing,

The Hudson, From the Wilderness

to the Sea. 1866 |

Transportation in the Hudson region was arduous before the introduction

of steam-powered boats. Travelers and trade goods moved unpredictably,

often stalled by unfavorable winds on the river or mired in

the muddy roads paralleling it. Steamboats' ability to carry

passengers and freight between New York and Albany on schedule

revolutionized water travel and ushered in a new age of technological

advancements in transportation.

Water transportation and travel were at a peak in 1850, when

railroads began to compete for freight and passengers. While

trains never completely replaced riverboats, they represented

the next level of improvement in transportation engineering

and ease of travel. For the first time in the Hudson's history,

land travel was superior to that on water, and freight traffic

and tourism both increased significantly. Fortunately for tourists,

the Hudson River Rail Road hugged the shoreline and was nearly

as scenic as the boats.

TOURISM

|

Tourists came from all parts of the United States and

Europe to see the Hudson. It was an important leg in trips

to Saratoga Springs, the Adirondacks, Niagara Falls, and

Canada, as well as a destination itself, particularly

in the Catskills where many tourist hotels were located.

West Point and other Revolutionary War sites were as popular

with visitors throughout the 19th century as they are

today, but for most travelers, the region's natural scenery

and its splendid river houses were the principal attractions.

These sights were best appreciated from the water. Most

tourists visited the Hudson River without stepping ashore

between New York City and Albany. Passenger

boats became ever larger and faster as the century advanced.

Eventually, the 150-mile trip was made within a single

day. There were day boats and night boats; from the latter

shoreline landmarks were viewed by searchlight.

|

|

'View

at De Koven's Bay.' From Benson J. Lossing,

The Hudson, From the Wilderness to the Sea. 1866

|

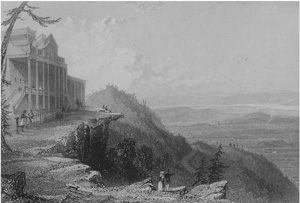

View

from the Mountain House, Catskill. Steel

engraving from watercolor view by William

H. Bartlett. From American Scenery. 1840.

|

|

Once in Albany,

some travelers headed west to Niagara on Erie Canal packet

boats or overland through the Mohawk River Valley; others

went north by canal to Lakes George and Champlain and on

to the Adirondacks. Travelers to the "Springs"

at either Ballston or Saratoga enjoyed the luxury of one

of the earliest railroads in America. These travelers used

guidebooks to direct them through New York City, to the

boats, and on up the Hudson, as well as to point out landmarks

along the way. |

While foreign travelers tended to head through the region,

the Hudson River hosted tremendous numbers of New Yorkers looking

to escape the city and engage with nature. This pastime was

popular with elite and common people alike, for the river's

advanced transportation services made it easy for city dwellers

of all classes to visit in the country if only for a day. Overnight

and long-term visitors stayed in hotels on the Palisades and

in the Hudson Highlands, two of the more dramatic scenic areas

in close proximity to the city. Inexpensive excursion boats

transported day-trippers.

ART & LITERATURE

'The

Hudson at "Cozzen's." ' Wood engraving by Harry

Fenn. From Picturesque America. William Cullen Bryant,

ed. 1872.

|

|

Prominent among Hudson River recreationists were artists

and writers. Wrapped up in Romantic sensibilities, they

attempted to capture the intangible essence of the region's

picturesque natural landscape in image, verse and prose.

The combination of a great reservoir of artistic talent

in the city and the proximity of the Hudson's sublime

scenery resulted in one of the most productive and significant

eras of art and literature in American history.

The artists who created the legendary canvases of the

Hudson River and Catskills in this era are known as the

Hudson River School. These painters, such as Thomas Cole

(pictured with poet William Cullen Bryant in Asher B.

Durand's 1849 painting "Kindred

"Spirits", Frederick Church, Sanford Gifford,

William Kensett, and Jasper Cropsey were very familiar

with the dramatic rustic locales and the taste of wealthy

city patrons. Each year to great fanfare, new works were

displayed in fashionable art galleries in the city. The

most popular paintings were quickly engraved on steel

plates and printed by the hundreds for sale to audiences

of more modest means. Prints and illustrations also helped

to maximize the financial return painters received from

their successful works.

|

Asher B. Durand was

New York's premier engraver, as well as a painter; but other

engravers and lithographers created Hudson River views for

reproduction and publication. Illustrating the vast scale

of this industry, it was prints of New York and Hudson River

scenes that established the reputation of the renowned American

lithographers and publishers, Currier and Ives, and they

were only one of many firms engaged in the business. In

1874, poet and publisher William Cullen Bryant edited Picturesque

America, a two-volume compendium of essays and poetry by

writers well-known in their regions, illustrated by wood-engravings.

- Prints and illustrations, from the 1820s to 1874,

representing the most popular images from the era are

presented in: Prints

and Guidebooks

|

|

The

Catterskill Fall. Steel engraving from watercolor view

by William H. Bartlett. From American Scenery.

1840.

|

|

'Newburg'

Aquatint of watercolor by William Guy Wall. From Hudson

River Port Folio. 1820

|

|

French

artist Jacques Milbert toured the Hudson River region in

the 1820's and compiled a series of colored drawings of

views he encountered on his trip. Upon his return to Paris,

he wrote an account of his travels that was published illustrated

with lithographs of the views. This publication introduced

the beauties of the Hudson River to the European public.

Thirty of the fifty-four views depict the region and are

included here. William Henry Bartlett, an English watercolorist,

made his first trip to North America in 1836 and began producing

colored drawings of views made popular

by American and European travelers. |

In 1840, a two-volume compendium of steel engravings of these

views was published simultaneously in London and New York with

the title American Scenery. Novelist Nathaniel Parker Willis provided

Romantic descriptions for the 118 views. Numerous engravers were

employed to create steel engravings of Bartlett's views. Forty-seven

views of the Hudson River region are included here.

| Poet

and publisher William Cullen Bryant edited a two-volume

work about the United States, which included essays by writers

well-known in their regions, each illustrated by wood engravings

of prominent views. Views from the five chapters dealt with

the Hudson River region and are included here.

In the last half of the 19th century, photography and

photographic duplication processes quickly supplanted

the hand-made, mechanically-reproduced prints that had

made the images of Hudson River popular

for previous generations. In some cases, traditional views

were reproduced, but the advent

of photography generally changed the way the river was

represented. Romantic,

|

|

West

Point and the Highlands.' Steel engraving from painting

by Harry Fenn. From Picturesque America. William

Cullen Bryant, ed. 1872 |

pastoral views were few; documentary and action-based

images were more the norm. Some very early photographs of subjects

and scenes in the Hudson River region are contained in the Photography

section of the Collections. There is also a link to the extensive

digital presentation of the NYPL Dennis Collection of stereograph

views of New York, Small Town America, where hundreds of images

of the Hudson River can be found.

Scene

from the 'Legend of Sleepy Hollow,' by Washington Irving.

Hudson Legends edition, 1867

|

|

The Hudson River

was also the source of an indigenous American literature.

Within the young nation Washington Irving is considered

the first man of letters to emerge, his renown based on

his Hudson River tales published in 1819-1820.

- Prose sections of American Scenery (1840) by novelist

Nathaniel Parker Willis and Picturesque America (1874)

by poet William Cullen Bryant are presented in searchable

text format

In the 19th century, American writers began to look back

on the history of the Hudson and reflect on its significance.

They, along with the artists, were motivated by a desire

to create a cultural identity for the nation. The river's

central role in New York's particular Dutch colonial history,

the Revolutionary War, the construction of the Erie Canal,

and the growth of commerce and industry provided historians

with gripping subjects.

The region's most important 19th-century chronicler, Dutchess

County native Benson J. |

Lossing (1813-1891) traveled the length of the

Hudson recording its historical events and sketching its natural

and cultural landmarks. In 1866, Lossing published The Hudson,

From the Wilderness to the Sea with more than three hundred wood

engravings, an encyclopedic compendium that continues to captivate

its readers.

-

Consult Benson J. Lossing's 1866 history of

the Hudson River in searchable

text

| In the 19th century,

writers were beginning to look back on the history of the

Hudson and reflect on its significance. This was also motivated

by a desire on the part of American artists and writers

to create a cultural identity for the nation. The river's

central role in New York's peculiar Dutch colonial history,

the Revolutionary War, the construction of the Erie Canal,

and the growth of commerce and industry provided historians

with gripping subject material. A searchable text version

of Benson J. Lossing's 1866 history of the Hudson River

can be found in the History

section of Collections. |

|

Street

View in Ancient Albany. From Benson J. Lossing. The Hudson,

from the Wilderness to the Sea. 1866. |

|