|

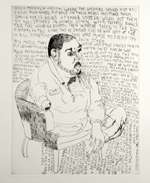

Humanities and Social Sciences Library > Collections > Print Collection > Multiple Interpretations Multiple InterpretationsArtists: H–ZDaniel Heyman (American, born 1963) In March 2006, in Amman, Jordan, Daniel Heyman joined a team of lawyers from the Center for Constitutional Rights and Susan Burke from the Burke O’Neil law firm; a journalist; and a portrait photographer to record interviews with Iraqis who had been detained in Abu Ghraib prison. The lawyers were gathering information to prosecute their ongoing class action lawsuit on behalf of the former prisoners against companies under contract with the U.S. Army. Heyman made eight drypoints, incising portraits and commentary in reverse on the metal plates as the men spoke. The artist said, “I wrote as fast as possible so as to give my viewers a real sense of the testimony given. I did not edit, other than to decide when to start writing and when to stop.” Words describing torture and humiliation crowd around the portraits and fill the sheets, visually imprisoning their subjects. Heyman’s line is taut and austere, seemingly so as not to soften the impact of his images. All the men had eventually been released without ever having been charged with a crime. In separate incidents since these interviews, two of the subjects have been killed by unidentified gunmen.

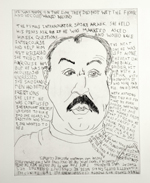

Diane E. Jacobs (American, born 1966) Diane Jacobs asked women friends, relatives, and strangers to recall the worst names they had ever been called. This survey and several dictionaries of slang provided the list, which she overlaid onto ten photolithographs of women’s faces. The verbal assaults encompass race, ethnic origins, religion, and slang for various parts of the body. The artist makes clear that the degrading slurs bear no relationship to the women, but “by hand setting and printing these words on a powerful woman’s face I challenge the viewer to question why these words exist and how we use them.” The portraits and the elegant letterpress type are printed in a subtle range of grays and jar with the vitriolic and scabrous text, serving the artist’s intention to “expose the tenacious, white, patriarchal power structure using language as my witness.”

David Levinthal (American, born 1949) Since the early 1970s, David Levinthal has arranged toys and dolls in miniature tableaux and photographed them as a way to consider national myths, American icons, and controversial and politically charged subjects ranging from the Holocaust to racial and sexual stereotypes. In this portfolio he recreates scenes from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, using 19th-century lead figurines (apparently illustrating the novel) that he found in a Paris flea market. Only the foreground is in sharp focus; all other details blur and merge with a black background, leaving Eva, Topsy, Tom, and Aunt Ophelia to act out their dramas on a mysterious, timeless stage. Levinthal appropriately chose to reproduce his photographs in photogravure, a 19th-century printing process that captures the luminous sheen of the lead figures.

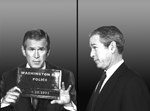

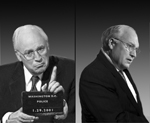

Nora Ligorano (American, born 1956) and For more than twenty years, Nora Ligorano and Marshall Reese have used art to address political and social issues. In Line Up, present and former high-ranking government officials, including George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, Donald Rumsfeld, Alberto Gonzales, and Karl Rove (Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz are not on view here), appear in a series of fake mug shots. They hold slates inscribed with numbers that refer to specific dates when the “suspects” made “incriminatory” statements about Iraq. President Bush in his State of the Union address on January 28, 2003, reported, “Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa…. He clearly has much to hide.” On January 25, 2002, Alberto Gonzales reported to President Bush, “[t]his new paradigm renders obsolete Geneva’s strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners and renders quaint some of its provisions.” In an accompanying DVD, these and other officials are heard making their assertions; the pop of a flashbulb is then followed by the mug shot of the speaker, growing progressively larger until it more than fills the screen. The screen goes dark, and a metallic clunk, presumably the sound of a prison door slamming shut, ends each sequence.

Olaf Nicolai (German, born 1962) In his sculpture Die Flamme der Revolution, liegend (in Wolfsburg) (2002), Olaf Nicolai appropriated an earlier monument by Siegbert Fliegel, Flamme der Revolution, commissioned in 1967 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. Fliegel’s concrete sculpture, installed in a public space in Halle in the former East Germany (Nicolai’s birthplace), was a vertical flame, painted red (documented in the color photograph). In his sculpture, on view in the Städtische Galerie Wolfsburg, Nicolai turned the vertical flame on its side. For Nicolai the Revolution has “fallen asleep” and may be enjoying some relaxation time in Wolfsburg, a city founded by the Nazis in 1938 as Stadt des KdF-Wagens (“City of the KdF Car”) and renamed after World War II. KdF, an abbreviation of Kraft durch Freude, or “strength through joy,” was the German state-controlled “leisure organization,” which developed the KdF-Wagen, later known as the Volkswagen Beetle. In this series of computer-generated prints, Nicolai further elaborated upon the transformation of the flame: the flame is flying, declaring its independence, liberated from any particular ideology.

Thomas Nozkowski (American, born 1944) Thomas Nozkowski refers to his quirky abstractions as “conundrums.” In addition to painting small, easel-size canvasses, Nozkowski also draws and, since 1990, has occasionally made prints: etchings and woodcuts, which like his paintings are populated by biomorphic and geometric forms, lines, and squiggles. This suite suggests the inventiveness and variety of his fresh, seemingly spontaneous arrangements of colorful shapes and patterns.

Andrew Raftery (American, born 1962) Andrew Raftery included himself and his partner, Ned, in Suit Shopping (in the background of the right panel of the diptych) for “it was important for me to be in there like a narrator in a Henry James or Jane Austen novel.” He offers a commentary on the social conventions of shopping in an upscale mall. In the triptych he shows the customer being fitted, flanked by scenes of the girlfriend “accessorizing” the purchase, and the buyer, in the privacy of the fitting room, admiring himself. In the diptych the couple peruse the shop and are waited upon by an attentive salesman. Suit Shopping attests to Raftery’s appreciation of earlier narrative prints, including Hogarth’s social commentaries and Moreau le Jeune’s series of prints describing aristocratic life in 18th-century France. His technical style of engraving pays homage to the French 17th-century printmaker Claude Mellan. Raftery turned to this now rarely used medium because he believes that “engraving itself is like a man’s suit—a cultural remnant, an icon of power. We still recognize it as authoritative because of its relationship to currency.”

Julião Sarmento (Portuguese, born 1948) Julião Sarmento’s response to the human figure can be unsettlingly ambiguous—are his subjects objects of desire or victims of violence? In this suite he elicits, almost viscerally, the sense of touch: fingers and hands clasp, touch, prod, and conceal. Even those prints that are more abstract are almost all charged with smudges and pentimenti that affirm the presence of the artist’s hand. The final etching is printed a dense, impenetrable black: a reference to death or to Sarmento’s painting, in which he used dust as a pigment (perhaps a reminder that ashes return to ashes, dust to dust?). Paralleling the artist’s enigmatic visual narrative, Stuart Morgan’s text describes an installation by Sarmento in a “House with the Upstairs,” which included the dust painting. Morgan associates the installation with the story of Penelope, who as she waits for the return of her husband, Ulysses, must fend off the attentions of numerous suitors. She promises to choose a lover from among them when she has completed her weaving, but each night secretly unravels the work woven that day. Artist and writer seem to meet in a common ground of erotic imagery, vulnerable flesh, and sexual, but unsatisfied, desire.

David Shrigley (British, born 1968) David Shrigley first received critical attention for his artist’s books and printed ephemera (he is also a painter and sculptor). His childlike illustrations provide just enough information to elicit humor and pathos simultaneously, leaving the viewer free to concoct a variety of scenarios that fit the cryptic imagery. Shrigley has commented about his humor, “I don’t set out to be funny in the first place. I set out to be profound. It just ends up being funny.” The prints in this portfolio do not suggest a single narrative; rather, each etching is a self-contained drama.

Juan Uslé (Spanish, born 1954) Juan Uslé’s paintings have been described as “a seemingly effortless combination of geometry and gesture.” In blumania, his first prints, gesture appears to win over geometry. In the course of this series, Uslé’s abstract images become increasingly rich and complex. He skillfully used printmaking processes like liftground, whiteground, and spitbite aquatint, which allowed him to approach the copper plate with freedom and spontaneity to realize painterly effects. The blue areas are not printed, but rather are handmade ultramarine gampi paper, affixed to the white backing paper with glue during the printing process.

John Wilson (American, born 1922) John Wilson responds here to Richard Wright’s story about Mann, a black man who dies trying to save his family during a storm, a victim not of nature, but of racism. The son of a follower of black nationalist Marcus Garvey, Wilson was introduced at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to the work of Daumier, George Grosz, Ben Shahn, and Picasso, artists who addressed social issues, but it was the politically charged paintings of the Mexican muralists that especially impressed him. In Paris, at the Museum of Man, he discovered the art of African and other non-Western cultures, and later he studied and worked in Mexico. “Along with looking and listening I began to read. Orozco paintings told it like it was! So did the stories of Richard Wright!” In 2001 Wilson provided four color aquatints for the Limited Editions Club edition of Wright’s Down by the Riverside. In this portfolio, issued separately, Wright included two additional prints, Death of Lulu and The Death of Mann, arguably the bleakest and most powerful images in the series.

Portfolios by the following artists were not shown in their entirely: Christiane

Baumgartner; Sandow Birk; Chris Burden; Olafur Eliasson; Elliott Green;

Daniel Heyman; Diane E. Jacobs; David Levinthal; Nora Ligorano and Marshall

Reese; Olaf Nicolai; Julião Sarmento; David Shrigley. |