Section Three

17 OLYMPIC GAMES

17 OLYMPIC GAMES

Lewis Wickes Hine (American, 1874–1940)

The Greek Wrestling Club at Hull House, Chicago

1910. Gelatin silver print

Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division

of Art, Prints and Photographs, Photography Collection

Founded in Chicago in 1889 by social reformer Jane Addams,

Hull House was among the first settlement houses in the United

States dedicated to serving the needs of immigrants and their

families. In addition to providing educational functions from

kindergarten to college-level extension classes, Hull House

included craft workshops, playgrounds, and, as seen in this

photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine, a gymnasium as the home for

its Greek Wrestling Club.

Wrestling was one of the main competitive sports in the original

Olympic Games, as well as in the revived Olympiad of 1896.

In contrast to the modern-day ideal notion that the winner

of a match should be decided by a demonstration of superior,

play-by-the-rules skill and strength, in some forms of wrestling

in the ancient games the victorious contestant often ended

up with the olive wreath by exercising a vicious, bloody, no-holds-barred

attack upon his opponent.

18 OLYMPIC

GAMES

18 OLYMPIC

GAMES

"Discus Thrower," plate 307 from:

Eadweard Muybridge

(English, 1830–1904)

Animal Locomotion. An Electro-Photographic

Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Movements. 1872–1885

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1887

11 volumes

with 781 photographic plates

Plates printed by the

Photogravure company, Philadelphia

Miriam and Ira D. Wallach

Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, Photography Collection

The discus throw, mentioned by Homer in both the Iliad and

the Odyssey, was one of five events (also including

the footrace, long jump, javelin throw, and wrestling match)

taking place on the same day in the pentathlon in the ancient

Olympic Games. The discus throw was reintroduced in the modern-era

revival of the Olympics as a Track and Field event. The bronze

sculpture of the Diskobolos, caught in fleeting action

by the fifth-century sculptor Myron, remains one of the most

ubiquitous images in all of Greek art.

Eadweard Muybridge, who immigrated to the United States around

1852, worked as a bookseller early in his career. After studying

photography, Muybridge, describing himself as an artist-photographer

and adopting “Helios” as his artist’s name, made a reputation

with his spectacular views of Yosemite and other scenic western

sites. Later, he made many systematic analyses of moving figures

(humans and animals) by taking sequences of photographs with

banks of cameras fitted with high-speed shutters.

While encouraging the aura of scientific investigation to

surround his work, Muybridge also sought to convey the serious

overtones of history by adapting the movements of athletic

competitions from the ancient Olympic Games as references for

his contemporary stop-action experiments, as may be seen here

in the twenty-four shots of an athlete photographed in the

act of throwing a discus.

19 THE

ACROPOLIS

19 THE

ACROPOLIS

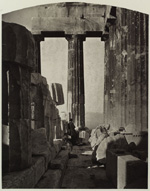

William James Stillman (American, 1828–1901)

The Acropolis of Athens, illustrated picturesquely and

architecturally in photography

London: F. S. Ellis, 1870

Album of 25 mounted photographic

plates, with descriptive letterpress text

Miriam and Ira D.

Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, Photography

Collection

The Parthenon, the temple dedicated to the virgin warrior

goddess Athena Parthenos situated atop the Acropolis in Athens,

is the most renowned building to survive from the ancient world.

By the fifth century B.C.E., the Acropolis had evolved over

the centuries from a citadel fortress to the site of sanctuaries

and memorials, the locus of enlightened civic government, and

the experimental birthplace of democracy. Pericles (ca. 495–429

B.C.E.), the virtuous Athenian statesman largely credited with

instituting a form of popular vote and with forging the cultural

and political supremacy of Athens over other city-states, instigated

construction of the Parthenon in 447 B.C.E. The Parthenon and

its setting included Pheidias’s gold and ivory cult statue

of Athena, a temple devoted to Victory, the Erectheum, and

the Propylaea, the monumental gateway leading to the sacred

precinct. It is impossible to overestimate the architectural

legacy of the Parthenon throughout the Western world – its

innovative plan, harmonious use of the Doric order, the lavishness

of its mouldings, and the awesome scale of its sculptural program.

Following early careers as a painter associated with the Hudson

River School and as founding editor of the art journal the Crayon,

William James Stillman took up photography in 1859. Continuing

as a journalist and travel writer abroad, Stillman put his

skills as a photographer to use while serving as consul in

Rome and Crete. His major achievement in the art of photography

was the series of twenty-five technically and formally beautiful

photographs that appeared in The Acropolis of Athens.

Ten are shown here, identified by Stillman’s corresponding

captions.

a. The Acropolis, with the theatre of Bacchus.

View taken from the proscenium of the theatre. The architrave

of the Parthenon is seen above the fortification wall.

b. Western façade of the Parthenon. At the right is Hymettus,

at the left the summit of Lycabetus is seen, and at the

extreme left is the Erectheum. The débris in the foreground

are architectural and sculptural fragments.

c. The eastern façade of the Propylaea. The island

and bay of Salamis are seen through the central intercolumniations,

and through those at the left of the port of Peiraeus.

d. Interior of the Parthenon, taken from the western gate.

The circular grooves are those in which the bronze valves

swing.

e. Western portion of the Parthenon. The names scratched

on the columns are of the Philhellenes, who fought here in

the war of Greek independence.

f. Eastern portico of the Parthenon, view looking northward,

and showing Mount Parnes in the extreme distance.

g. Eastern façade, or front, of the Parthenon.

h. Interior of the Parthenon, from the eastern end; at

the left, in the distance, is seen the island of Aegina.

i. View … looking eastward over the ruin of the

Parthenon. Modern Athens is seen at the left, and above it,

in the centre, Lycabetus; at the right Hymettus, and in the

extreme distance, Pentelicus.

j. View of the Acropolis, from the Musaem Hill.

A portion of modern Athens, is visible at the left; at the

right is seen the course of the Ilissus, and the remaining

columns of the Temple of Jupiter, beyond which rises Mount

Hymettus. The view is eastward.

20 GIORGIO DE CHIRICO

Giorgio de Chirico (Italian, born in Greece, 1888–1978)

The Return of the Prodigal Son I, from a series of

six lithographs, Metamorphosis

1929. Lithograph printed in three colors

Published by Editions

des Quatre Cjemins, Paris

Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division

of Art, Prints and Photographs, Print Collection, Norrie Fund

Giorgio de Chirico, most often identified as the founder of pittura

metafisica and crucial to the early development of surrealist

painting, was born in Vólos, Greece, the port city from which

Jason and the Argonauts were said to have departed in their

quest to regain the Golden Fleece. Both de Chirico and his

younger brother Andrea (the painter and composer who later

adopted the name Alberto Savinio) received their artistic

training with some of the most prominent Greek painters and

musicians of the time in Athens, where de Chirico continued

to live until his father’s death in 1905. Greek art and culture

remained deeply rooted in de Chirico’s art throughout his

long, contentious, and richly varied career.

The Return of the Prodigal Son I (mistakenly called Socrates when

acquired by the Library in 1946) is one of numerous works,

including several related paintings entitled the Archaeologists,

in which de Chirico creatively adapted elements from classical

Greek architecture to construct his figures. In this lithograph,

as the ghost-like wayward son stands by, the father sits rigidly

in his armchair, his torso, upper arms, thighs, and top hat

composed of Ionic columns, voluted capitals, and temple pediments.

Knowing that ancient Greek architecture did not consist of

a collection of purely white marble temples, de Chirico indicated

traces of paint on the figure of the father that once would

have blazed with colors.

21 SIR WILLIAM HAMILTON

Pierre-François Hugues d'Hancarville (French, 1719–1805)

Antiquités étrusques, grecques et romaines … gravées

par F. A. David

Paris: Chez l'auteur, 1785–87

Four volumes in 24 parts,

with 289 etching and aquatint plates

The George Arents Collection

of Books in Parts

Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803) served George III as British

ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples for over thirty years,

a period when archaeological excavations, antiquities trading,

and the pillaging of tombs were rife in southern Italy and

throughout the Hellenic world. From the time of his arrival

in Naples, Hamilton began amassing a vast collection of classical

art and artifacts. In 1772, he sold to the British Museum 730

Greek vases and 175 terracottas, as well as glass, bronzes,

gems, and thousands of coins, forming part of one of the richest

collections of ancient art in the world today.

In 1766, Hamilton commissioned Baron d’Hancarville, an antiquary

(and evidently a small-time criminal), to catalogue and publish

his collection of vases, which appeared in four sumptuously

illustrated, oversized volumes. New editions followed, including

this French edition of 1785–87 in greatly reduced format (four

of twenty-four separately issued parts are shown). Open here,

vol. 1, plate 9, depicts preparations for the marriage of Helen

and Paris on a vase found at Capua; vol. 3, plate 25, according

to d’Hancarville, is a scene from the Feast of Dionysus.

The plates in Hamilton’s catalogues, representing only a small

part of the collection, reproduced a wide range of subjects,

including legendary Greek heroes, gods and goddesses, athletes,

and architectural elements. The subjects of the vases, their

frieze-like compositions, and the crisp linearity in which

they were drawn exerted enormous influence on the emerging

neoclassical style in ceramics, interiors, architecture, decorative

motifs, and major works by Flaxman, David, Fuseli, Ingres,

Girodet, Joshua Wedgwood, and countless other artists.

22 SOPHOCLES

Sophocles (ca. 496–406 B.C.E.) and Eduard Bargheer (German,

1901–1979)

Antigone. In der Übersetzung von Karl Reinhardt

Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Ars librorum, Gotthard de Beauclair,

1967

Artist’s book with 10 etchings and one etching and aquatint

on front cover by Eduard Bargheer; printed by Arnd Maibau,

Berlin. No. 40 of 200 copies

Spencer Collection

Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone (written in 442 B.C.E.)

was performed by three rather than the traditional two actors,

which represented the playwright’s major dramatic innovation.

Prior to the beginning of the play, Antigone, daughter of Oedipus,

former king of Thebes, has lived in exile for many years with

her blind father. In the play, King Creon, Antigone’s uncle,

decrees that the corpse of the slain traitor Polyneices, her

brother, must not be buried. Antigone defies the order and

is sentenced to death. Although betrothed to Creon’s son Haemon,

she is buried alive in a cave. After the blind prophet Tiresias

reveals that the gods have sided with Antigone against him,

Creon relents, but only after Antigone has already hanged herself.

Haemon attacks his father and kills himself. Creon's wife,

Eurydice, then commits suicide, leaving Creon alone with his

niece, Antigone’s sister. The frequent subject of contemporary

reinterpretations, Antigone was recently described in

a New York Times review of a five-part, fragmented production

as “a Theban tear-jerker,” and the “ultimate story of a dysfunctional

family.”

On the front cover of his illustrated edition, German painter

and printmaker Eduard Bargheer has portrayed Antigone with

the stony face, staring eyes, enigmatic expression, and hairstyle

of an Archaic period korê, the female sculptural counterpart

of Picasso’s kouros in Pindare.

VIIIe Pythique, exhibited (#16) on the other side of

the gallery.

23 ARISTOPHANES

23 ARISTOPHANES

Aristophanes (448?–385? B.C.E.) and Frantisek Kupka (Bohemian,

1871–1957)

Lysistrate … traduit du grèc par Lucien Dhuys; gravures

originales de François Kupka

Paris: A. Blaizot, 1911

Illustrated with a full-page frontispiece

and 19 headpieces in etching and aquatint printed in colors à la poupée;

extra double suites of the etchings and 12 wood engravings.

No. 42 of 100 copies on Japon impérial paper from a total

edition of 250 copies

Spencer Collection

Lysistrata (411 B.C.E.), a troubling mix of gravity

and farce, is one of the greatest and still most frequently

performed comedies from antiquity. In his play, Aristophanes

openly mocked the political leaders and citizens of Athens

who supported a twenty-year war against Sparta. The playwright

imagines a strike by the women of Athens, instigated by Lysistrata,

who seize the Acropolis and the city’s treasury, and then reject

all sexual advances by their husbands as long as the war continues

to be waged. The men of Athens, in agony over their sex-starved

condition, are forced to capitulate and to negotiate the peace.

Kupka visualizes the plot of the play by presenting a frieze-like

procession of animated characters across the upper margins

of fifteen pages, including here, in a double-spread lineup,

a cross section of distressed Athenian men. For too long viewed

merely as a pioneer of abstract painting, Kupka, early in his

career, was also an extremely witty and incisive illustrator

of texts, as Lysistrate vividly demonstrates.

24 AESCHYLUS

Charles-Marie-René Leconte de Lisle (French, 1818–1894)

and Frantisek Kupka (Bohemian, 1871–1957)

Les

Erinnyés: tragédie antique … illustrée des compositions

et gravures à l’eau forte de François Kupka

Paris: A. Romagnol,

1908

Two-part play, illustrated with 75 etching and aquatints,

and head- and tailpieces, with additional plate proofs in pure

etching and before the letters, and 22 wood engravings. No.

1 of 10 large paper copies on Vélin d’Arches paper from a total

edition of 300 copies; and with one full-page watercolor and

18 watercolor vignettes

Spencer Collection

The leader of the nineteenth-century Parnassians, French poets

recognized for the classical restraint and technical perfection

of their works, Leconte de Lisle translated and adapted Aeschylus’s

trilogy the Oresteia for a contemporary audience. In

Leconte de Lisle’s two-part adaptation Les Erinnyés,

the furies (les erinnyés), minor goddesses who specialize

in enacting revenge upon the evildoers of the world, torment

Orestes for murdering his mother, Clytemnestra, who had killed

his father, Agamemnon.

In copy 1 of Les Erinnyés, shown here, Kupka embellished

the lower margins with a series of colorful watercolor vignettes

of the principal and supporting characters, in addition to

sea monsters, rollicking mermaids, tumescent satyrs, seductive

sirens, and raping centaurs. On an elaborately decorated inserted

sheet, he dedicated the copy to “ma chère Ninie” (Eugénie Straub),

his future wife.

Next Section