The New York Public Library, Berg Collection of

English and American Literature

The 1867 Pocket Diary: Traces of a Very Private Man

Edgar Johnson begins his classic biography with the observation that "Charles Dickens belongs to all the world." But Dickens wanted the world--and posterity--to possess the work, not the life. And so, in early September 1860, in a field behind Gad's Hill Place, he made a great bonfire of nearly his entire correspondence. Only those letters on business matters were spared; and as he watched the fire, how he wished that every letter he had ever written were part of the conflagration! (After Dickens's death, Georgina Hogarth would keep a sharp eye out for anything compromising.) Dickens's little Almanack for...1867 miraculously survived the general fate of his private papers (the flames) only because, late in December, it was either lost or stolen in New York City during the American tour. Resurfacing more than fifty years later at a New York auction house, it was purchased by the Berg brothers along with other Dickensiana, and is now a prized part of the NYPL collection that bears their name.

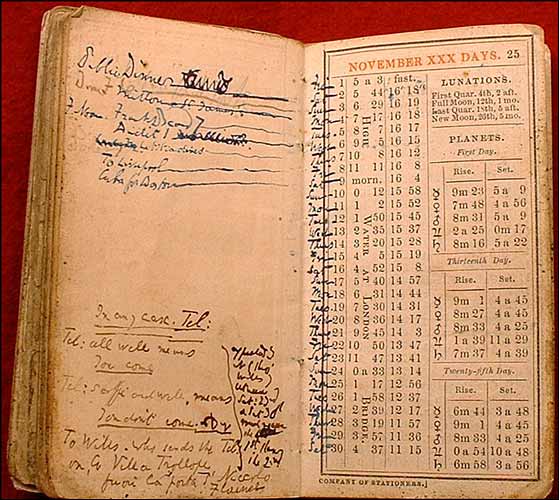

Dickens's 1867 pocket diary for November with, on the left-hand page at bottom, the coded texts of two telegrams: "all well" meant that Ellen should join him in America during his reading tour; "safe and well" meant "don't come." Through such elaborate ploys as coded telegrams and the like, Dickens managed to keep his nearly 12-year affair with Ternan a secret. Only those closest to him knew about his "Dear Girl." After his death they uniformly maintained a discrete silence, while the keepers of the flame, John Forster and Dickens's ever-vigilant sister-in-law, Georgina, did their best to obliterate Ternan from the record. Nevertheless, it could not be denied that in his final will, Dickens named her as the first legatee: "Miss Ellen Lawless Ternan, late of Houghton Place, Ampthill Square, in the county of Middlesex," was bequeathed one thousand pounds.

1 2