|

When Is a Book Not a Book? Oliver Twist in Context Section 2. Magazines and Collaborative Authorship

To assess proprietal and editorial interventions in Oliver Twist, we need first to recall that the proprietor, Richard Bentley, had started up his magazine as a rival to his former partner Henry Colburn's successful New Monthly Magazine. Bentley, determined to outdo the competition, aimed at capturing the market for humor: Wit's Miscellany, he intended at first to call it. Then he changed to a name that links his own to that of the magazine's persona: Bentley's Miscellany. (One wag said the title was ominous—Miss Sell Any.) Humor, not politics, was, as the "Prologue" announced, the keynote of the venture. For contributors to this miscellany of papers melded together into Bentley's, Richard Bentley bought up the team who were making a decided hit with their humorous pen and pencil sketches of lower-middle-class urban life: Charles Dickens and George Cruikshank. Their success was in the sketch, something either visual or verbal that was quickly executed and quickly absorbed, and that recorded the evanescent and fugitive detail of modern life. The text of Oliver Twist, a long novel that is seldom humorous and that from the beginning attacks political measures, should be understood at the outset as a contribution that contrasts with the ostensible purpose and tone of Bentley's Miscellany and with Sketches by Boz, magazine and newspaper scenes and tales written by Dickens and subsequently, when collected into volumes, illustrated by Cruikshank. The magazine's purpose and tone, in turn, are defined against the competition, archly described in the "Prologue": We do not envy the fame or glory of other monthly publications. Let them all have their room. ... One may revel in the unmastered fun and the soul-touching feeling of Wilson, the humour of Hamilton ... and the Tory brilliancy of half a hundred contributors zealous in the cause of Conservatism. ... Elsewhere, what can be better than Marryat, Peter Simple, Jacob Faithful, Midshipman Easy, or whatever other title pleases his ear. ... In short, to all our periodical contemporaries we wish every happiness and success. ... We wish that we could catch them all.But, the "Prologue" continues, using the editorial first-person plural although the text was composed by a hired contributor, "Our path is single and distinct. In the first place, we have nothing to do with politics." Out of the context of a magazine promising "wit" and eschewing "politics," Oliver Twist loses some of its shock value. And unless we keep in mind the opening announcement that this will be a witty, nonpolitical miscellany, we may miss some of the underlying tension that surfaced in Richard Bentley's quarrels with Dickens about his contributions to the Miscellany, for Dickens was never so keen on eschewing politics as Bentley was. Yet only one scholar, Kathryn Chittick, in her Dickens and the 1830s (1990), has studied Bentley's Miscellany as an entity in its own right and indicated how the proprietor, through his choice of writers and selection of materials, promulgated his conception of a wit's miscellany. Moreover, proprietor and editor further shaped the contents of the journal by attempting to buy up the writers then making Fraser's Magazine so popular. They succeeded in hiring many of the contributors to Fraser's, including its outstanding editor, William Maginn, who wrote much if not all of the "Prologue." And then they signaled that coup in the "Prologue," hailing "the wit of our contributor Theodore Hook," "the fascinating prose or delicious verse of our fairest of collaborateuses Miss Landon," and "the polyglot facetiae of our own Father Prout." The contents of any issue of Bentley's, including its fiction, should be understood in the context of what other journals were publishing and what other writers and illustrators were available. To some extent authors and artists had their own styles, but to some extent too they were melded collectively into a house style, the polyphonic "miscellany" unifying into a "material whole." The best serial fiction in or out of magazines, such as Thackeray's Vanity Fair (published in 20 monthly numbers), exploits that verbal and visual polyphony.Dickens both edited and supplied text for Bentley's under the pseudonym "Boz," the author of Sketches by Boz. At the conclusion of his first contribution, about the mayor of the provincial town of Mudfog, Boz explains that "this is the first time we have published any of our gleanings from this particular source," that is, the Mudfog papers. He also suggests that "at some future period, we may venture to open the chronicles of Mudfog." This fiction of a manuscript source resembles that preserved through the first numbers of Dickens's concurrent monthly serial, The Pickwick Papers. Oliver Twist commences in the February number of Bentley's, under the title of Oliver Twist, or, the Parish Boy's Progress, by "Boz." As the first sentence of the story makes clear, this is a continuation of the Mudfog papers: Oliver is born in the Mudfog workhouse. Thus, naming Dickens as the author of Oliver Twist, as the first volume publication and the bookdealers' catalogues do, distorts the textual record and obscures the ways in which the narratorial voice, Boz, is constructed out of those voices that precede and surround it. That distortion was compounded when Dickens's authorized biographer, John Forster, made Oliver Twist into the first of three versions of Dickens's own childhood hardships, as if the story had its only origin in Dickens's own life. In fact there were other claimants for the originator of the story. Dickens's "coadjutor" on Sketches by Boz, George Cruikshank, may indeed, as he later said, have suggested to Dickens that they collaborate on a story about the rise of "a boy from a most humble position up to a high and respectable one." For 15 years, Cruikshank had wanted to illustrate a contemporary version of William Hogarth's narrative series of 12 pictures, Industry and Idleness. Hogarth's pictures track the parallel but contrasted fortunes of two apprentices: one, Francis Goodchild, through industry rises to "a high and respectable" position as Lord Mayor of London, while the other, Tom Idle, through idleness falls into bad company. Idle is eventually sentenced by his former fellow apprentice Goodchild and hanged on Tyburn Hill. A successful recent exhibition of Hogarth's work had made such a project more viable.

NYPL, Berg Collection William Hogarth contrasted the fates of an industrious apprentice (Francis Goodchild) and an idle apprentice (Tom Idle) in a series of 12 engravings published in October 1747. Here, Tom, after committing an armed robbery, is hiding from the law in a garret with a prostitute, who examines the loot. Tom is startled by the noise of a cat dislodging bricks as it chases a rat down the chimney.

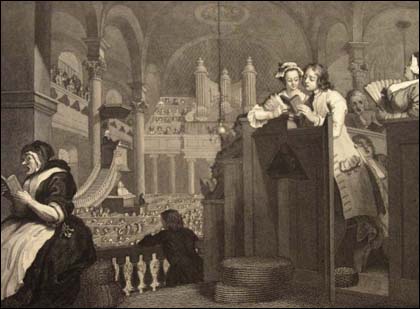

NYPL, Berg Collection Francis Goodchild attends St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, where he sings a psalm accompanied by a young woman who is his master's daughter and his own future wife. Hogarth complicates the apparent moral polarities of his pictures, but nineteenth-century interpreters tended to simplify and rigidify the contrasts, leaving out the ways that Tom and Francis pursue similar ends by different means. Another writer with a claim on Oliver's paternity is novelist William Harrison Ainsworth, who was from the 1830s to the end of the century a very popular writer, especially of fiction for boys. Dickens's closest friend, Ainsworth had put Boz in touch with the publishers, artists, and journalists who helped to make Dickens's early reputation. By 1836 Ainsworth had embarked on a series of novels exploring the lives of thieves. The first, Rookwood, about the famous highwayman Dick Turpin, had been reissued with illustrations by Cruikshank, who had also been interested for 17 years in collaborating with some writer on an illustrated life of a thief. The second, Jack Sheppard, about a romantic young burglar, overlapped Oliver Twist in Bentley's Miscellany. Ainsworth collected a lot of written and pictorial material about eighteenth-century miscreants, including James Sykes, a companion of Jack Sheppard and a possible inspiration for Bill Sikes. Dickens and Ainsworth were together frequently, discussing a slew of present and future projects. Yet Ainsworth's contribution to Oliver Twist usually goes unnoticed.

The point of all this is that in the magazine context Oliver Twist's authorship is a multiple thing. The proprietor, Richard Bentley; the editor, Charles Dickens; other journals, such as New Monthly and Fraser's Magazine; other contributors to Bentley's, such as the stable of Fraser's writers and those already being published by Bentley; the pseudonymous author "Boz," known for his "sketches" of metropolitan scenes, characters, and tales; the illustrator, George Cruikshank; pictorial progresses by Hogarth and his successors; and a close friend (and future editor of the Miscellany), Harrison Ainsworth—all influenced the subject, style, tone, and content of the serialized fiction. Serialization deconstructs the single author as sole creator, and does so as part of a larger collaborative project within which the serial is framed. Conversely, prioritizing the book as a single-authored material object over the multiply-authored serial deconstructs the periodical, erasing all the extratextual influences, turning the voice from polyphonic to monophonic and connecting the text to one author's imagination rather than to the culture of a magazine and of a historical moment.

|